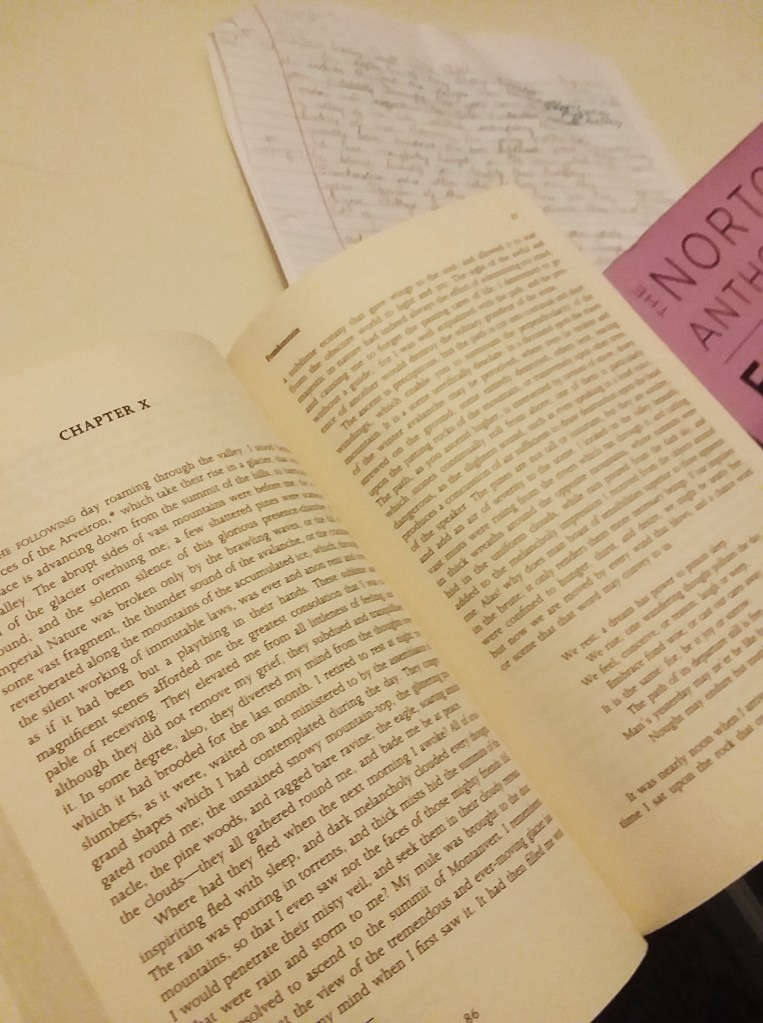

In chapter ten of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Shelley includes the final two stanzas from her husband, Percy Bysshe Shelley’s poem Mutability. Seemingly, this quotation comes at an inopportune and arbitrary time. In its entirety, Bysshe Shelley’s poem’s theme is that the only certainty in life is change, whether it be environmental or personal emotional change. The final two stanzas in particular highlight how fickle human emotions are.

Within the context of Frankenstein, these stanzas are included as an extension to one of Frankenstein’s many inner philosophical musings. His reflection lines up perfectly with the theme of Bysshe Shelley’s poem. He states that man thinks of themselves as higher beings due to the complexity of their emotions and thoughts when this impedes them in reality, thinking to himself, “if our impulses were confined to hunger, thirst, and desire, we might nearly be free” (Shelley 87). Because of this musing, the closing stanzas of Mutability which include the lines “We rest. –A dream has power to poison sleep; / We rise. –One wandering thought pollutes the day” (Bysshe Shelley 766) come to the mind of Frankenstein. However, the similarities in the texts and the symbolism of the poem do not end there.

At this time in the novel, Victor Frankenstein overlooks a valley of ice and solitude, contemplating the hubris of man. However, quite recently– at the most, a few months ago– Frankenstein’s young brother had been viciously murdered. Frankenstein’s dear childhood friend had been, as Frankenstein believes, wrongfully hanged for the crime. Blaming himself, he believes that the monster he created had murdered his brother. He had fallen into a deep depression that he could explain to no one surrounding him. Despite these tragedies, Frankenstein feels utter calm looking down on this scene. A walk through mountains and glaciers seems to have entirely cleared his mind of the preceding months of hardship. It would seem as though Frankenstein’s “yesterday may ne’er be like his morrow” (Bysshe Shelly 766). Though he enjoys thinking of himself as above other humans, Frankenstein is just as fickle as his imperfect peers.

In addition to the double entendres presented by the poem’s presence, the stanzas foreshadow the coming events. Finally, Frankenstein has found a location of peace far from his mistake and its consequences. He’s able to contemplate the faults of humanity once again, so he seems to be on his way back to being himself. After this time of misfortune and pain, Frankenstein has finally found tranquility. He shouts to the heavens, “‘allow me this faint happiness, or take me, as your companion away from the joys of life’” (Shelley 88). Just then, in classic horror-movie-monster fashion, Frankenstein’s monster comes barreling across the tranquil land of ice to rain on Frankenstein’s short-lived parade, reminding him of the horrible mistakes he’s made. Yet again, change seems to be the only constant within Frankenstein’s life. Each time he finds something to call his own, whether it be positive or negative, it seems impossible to hold on to it for long.

Works Cited

Bysshe Shelley, Percy. “Mutability.” The Norton Anthology of British Literature: The Romantic

Period. 10th ed. Stephen Greenblatt, General Editor. W. W. Norton, 2017. pp. 766

Shelley, Mary. Frankenstein. Introduction and Notes by Karen Karbiener. Barnes and

Noble, 2003.

Paige, “The Mutability of Frankenstein” presents a well-wrought and insightful exploration of the role that the last two stanzas of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s poem “Mutability” play in Chapter 10 of Frankenstein. Editing for brevity and more precise diction would make this strong analysis even stronger. Note that what you refer to as double entendre in the last paragraph is actually ambiguity.

LikeLike

Paige, “The Mutability of Frankenstein” shows your understanding of both “Mutability” and Chapter 10 of Frankenstein. With the strong introduction to both of the writings, a reader can see the knowledge of both. By going in depth of the events happening to Victor and his monster in paragraph three, also shows how Percy Shelley’s writing plays into that chapter.

LikeLike